|

Click to enlarge.

|

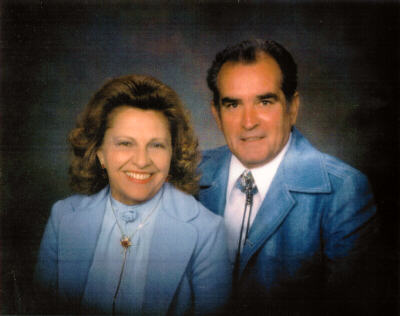

"Tough times never last. Tough people do." It's a message

you might expect to find carved in granite, but in the case of Frenchy and Carol Lagasse,

a note on the refrigerator works just as well.

The Lagasses have always taken inspiration where they can find it — from their work,

from each other and especially from their home in California's Pico Canyon, the place where

Chevron first took shape more than one hundred years ago.

[From 1967 to 1994 the Lagasses were] the lessees of the canyon, a narrow, steep-walled

slash in the Santa Susana Mountains just north of Los Angeles. This is where Alex Mentry,

the patron saint of Chevron field hands, brought in the first commercially successful oil well

west of Pennsylvania. The well, dubbed CSO No. 4, was the flagship of Chevron

predecessor California Star Oil Works — later reorganized as Pacific Coast Oil Company and

then the Standard Oil Company of California.

The Lagasses [lived] a mile down the road from CSO No. 4, which, with some wheezing

and groaning, still produced a barrel of crude [until 1990].* The surroundings are a veritable

museum of oil-field relics: old steam engines, a replica of a wooden derrick, the

100-year-old schoolhouse where the children of employees learned to read and write.

The Lagasses turned their thirteen-room home, built by Mentry himself in the 1890s, into

an inviting, antique-filled showcase that has been visited by more than 30,000 people since

the Lagasses started keeping a guest book in 1969.

Most of what remains in Pico Canyon was preserved, restored and,

on more than one occasion, rescued from the brink of dilapidation by the Lagasses. While

some of their efforts had financial support from Chevron, such as replacement of the

shingles on the "Big House" and the one-room Felton School, the bulk of the work

was completed with the Lagasses' own labor and money, including a $10,000 investment

during their first year alone.

"I've always had an interest in old things and what makes 'em tick," explains

Frenchy, a native Californian who in 1947 went to work for Chevron as a roustabout. A

quiet, self-effacing type who punctuates his bits of conversation with shy smiles, he's clearly

more comfortable doing things than talking about them.

Carol is his perfect foil: vivacious, red-headed and Texan, a doer and a

talker. As Bob France, retired production manager for the Pico area and himself an avid

preservationist, puts it, "She's the spark plug that has kept the history here alive."

Frenchy and Carol married in 1948, back when Chevron was paying its young field

hands $1.25 an hour ("You know we married for love," Carol laughs).

Eighteen years and three daughters later — Nanette, Laurette and Suzette — they made a

decision that changed their lives.

"We were just settling into a nice home in Saugus," Carol recalls, "when

one night Frenchy came home and told me the company was planning to tear down this

big old house in the canyon. I just about cried; it didn't seem right. So we made

arrangements to take it over."

The home, however, nearly took them over first. After Alex Mentry died in 1900, a

series of oil-field families, usually those of superintendents for Pico Canyon production, lived

in the company-owned structure. Some of the tenants were conscientious; others

considerably less so. By the time Frenchy, Carol and their three children obtained a lease,

birds and other less savory creatures had taken up residence. An entire boarded-up room

was infested with honeybees.

"Moving those bees out was one of the hardest things I ever did," recalls

Frenchy. For three months, he and Carol armed themselves with smoke, sprays and plenty

of netting to wage relentless war on the insects. The Lagasses finally beat the bees,

receiving just a few stings in the line of duty.

They also replastered, repainted and rewired most of the old home's interior, replacing

fifteen broken windows and spraying 55 gallons of paint onto the weather-beaten exterior

before it turned from gray to white. Another thirty gallons of paint were added the next

year.

Rescuing the rest of the canyon wasn't much easier. In 1967, when the Lagasses moved

in, they were the only residents along a three-mile stretch that had been home to a hundred

families in the 1890s. That had been the heyday of Pico production, when dozens of

wooden derricks dotted the hillsides and the settlement itself was known as Mentryville in

honor of its founder.

Production, however, fell off in the late 1920s. [Pico Field, part of the Southern Division

of Chevron USA's Western Region, produced eighteen to twenty-six barrels of crude a day

from eleven wells when this story was written.]* Mentryville residents disappeared,

sometimes hauling their wooden cottages with them. Not much of the old boom town

remained, and what did was ravaged by the brush fires that seem to sweep the Santa Susana

range as regularly as summer breezes.

Feeling like archaeologists, Frenchy and Carol went to work. They retrieved the old

bricks and nails that had once been Mentryville. They restored several of the remaining

structures — the Mentry barn, the chicken coop, even the old schoolhouse that at one point

fell into such neglect that it served as a stable.

The labor was arduous, especially for Frenchy, who by the late 1960s was a busy

production relief lead in the area surrounding Pico. The canyon was subject to droughts,

earthquakes, brush fires and occasional blizzards. Rattlesnakes crawled beneath the rocks

and bushes; one year Frenchy killed nineteen.

Every spring, the usually peaceful Pico Creek turned into a dangerous torrent. One year

it nearly swept the barn away; in an earlier era a piano inexplicably had come surging down

in its floodwaters. Carol recalls that she and the girls once stood on the bank holding onto

a rope tied around Frenchy's waist while he repaired a broken gas line that dangled over

the surging creek.

All this effort might not have been worthwhile if the Lagasses hadn't

taken such enjoyment from their living history lesson.

When Chevron personnel, both current and retired, heard about the restoration of the

canyon, they dropped by to offer help and share recollections and photographs for Carol's

ever-growing albums. From them and other area residents, the Lagasses gained a vivid

picture of what life in old Mentryville was like.

"There was always something going on," says Carol. "The town had a

blacksmith, a machine shop, even a public laundry. You could buy bread from an outdoor

bakery or get a whole meal at the boarding house for ten cents. A recreation center held

hoedowns and Shakespearean readings at night. They even had a gas-lit croquet field."

As for Alex Mentry, the founder of all this, "He was brilliant," Carol says.

"He created gas stoves where there was none before, and he engineered one of the

earliest pipelines used in the West. He equipped his home with gas lamps, running water

and indoor toilets — the envy of the area."

The resourceful Mr. Mentry probably would have commended the Lagasses for their

work in restoring "his" canyon. Today's Pico Canyon is so handsome and rustic

that film crews from Hollywood scout it out regularly.

Singer John Denver made a music video here, while Michael Landon filmed an episode

of the television series Highway to Heaven. And Mr. T, the burly, mohawked

star of TV and film, bounced the Lagasses' grandchildren on his knee and relaxed on an old

rope swing between takes of an A-Team segment made here.

Most visitors to the canyon are not celebrities, of course, but the Lagasses [welcomed]

them just as warmly, sometimes hosting entire bus loads at a time. A team of volunteer

guides often helps show the guests around.

"Everyone who comes here contributes something," says Carol. "The

old-timers will tell you something you didn't know about an antique in the house or the history

of the area. Just listening to people, watching them as they sit on a porch swing for the first

time since they were kids, gives you the feeling that what we have here is worth

saving."

The Lagasses actually started caring for the property in 1966. Frenchy and Carol's daughter Nanette remembers:

"We took over the house in mid-1966, spent the time restoring the things that we needed to make it liveable — years of honeybees in the walls of the two-room bedroom suite upstairs — and we moved in July 17, 1967, the same day as my paternal grandma's funeral. It still took years of renovation to get the house where it was comfortable for our family."

The Northridge earthquake of Jan. 17, 1994, displaced the Lagasses from the Big House. They moved into a motorhome on the property and Frenchy continued to serve as a paid consultant for Chevron USA's oil field shut-downs until

June 30, 1995, when the couple relocated to a vacation home in Lebec. Less than eight months later, on Feb. 10, 1996, while vacationing in Arizona, Frenchy died in his sleep. He was 72.

CSO No. 4, California's first profitable oil well, was also the longest continually operating

oil well in the world when it was capped off in September 1990 after a run of 114 years.

Mentryville and its surrounding acreage were donated in November 1995 by Chevron

USA to the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. Mentryville is a state park, open daily from sunup to sundown. To get to Mentryville,

follow Pico Canyon Road approximately three miles west of the Lyons Avenue exit off of

Interstate 5. Veer left when you come to the fork in the road and continue to the

designated parking area.

|